Okay, Mom. Sit down, this is going to be a whirlwind.

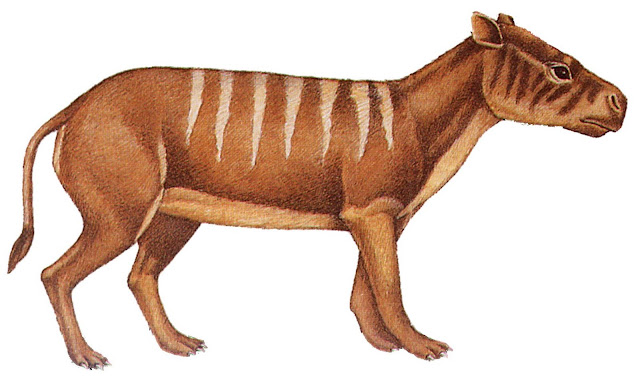

First off, this is an oreodont:

Cute, right?

Don't get too attached: they're dead now, as of about 5ish million years ago, but for most of the Cenozoic they were all over North America and about as common as deer, possums, or hippies are today. Their fossils were called the most common Cenozoic fossil of North America, a quote by Malcolm Rutherford Thorpe (an old dead guy your daughter has a science crush on) that Meaghan rides pretty hard for grant proposals.

Point is, these guys were everywhere, but their taxonomy is all sorts of disagreeable. You know how Dad used to get into fights with our family friends every Thanksgiving about which type of wood was best to burn, using no evidence except his own personal volume? Yeah, it's sort of like that - people don't really know how all the oreodonts are related to one another, but some people have some really strong opinions that they haven't backed up with things they've published. They say that one group is related to another group because of some funny tooth shape or skull bone, but there's no evidence that those differences are any more important to these species than our hair color is to us.

|

| Different species of Lohans? |

So your brilliant, super amazing, totally hireable-in-the-future daughter is using lots of math to find out which bones and shapes can say a species is a species, then she's going to rewrite the family tree of this group. But why, you most undoubtedly are asking, Why, Meaghan, does anybody care? Well other than because you LOVE ME, Mom, lets revisit the whole "most common fossil in the Cenozoic of North America" thing. Fossils are useful for loads of things, but since you like living animals lets talk about those.

|

| Endangered and Adorable |

See these guys? Yeah, they're dying out, and sometimes we don't always know why. Science can do a lot of things, but predicting the future is typically pretty difficult for it (see weather reports for details). To understand what things are making animals go extinct now, we need to know what made them go extinct in the past. Are there certain features that make a creature go extinct more readily? Which environments are more likely to lose members?

Well, we've got about 40 million years of watching oreodonts go nuts with their evolution and still fail to make it. Knowing why they died out can help us look for weak points in our modern ecosystems, and pinpoint which features spell Welcome to the Danger Zone to an adaptable, adorable hooved animal like the ones above. Evolutionary trends of the past 50 million years probably are repeating today, we just have to be able to find them. And to find them, we have to better understand how common organisms were related to one another, and how they changed over time.

Boom, Mom. That's the sound of your mind being blown by how awesome your daughter is.

Also have I mentioned lately how super intelligent and amazing and gorgeous you are? Because you're the best. And like, super nice. And cool. And amazing. Just FYI.

Also have I mentioned lately how super intelligent and amazing and gorgeous you are? Because you're the best. And like, super nice. And cool. And amazing. Just FYI.