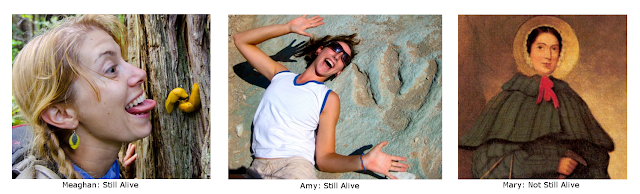

To understand this blog, there are three people that you

have to be introduced to: Meaghan Emery, Amy Atwater, and Mary Anning. Let’s

start with the ones that aren’t dead, because they’re the most exciting.

Amy Atwater and Meaghan Emery have known each other since

before anyone admitted that Amy was just never going to grow into her nose. At

the time, Amy was a camper at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry’s

Science Camps, while Meaghan was a counselor, sneaking off to get into trouble with Amy’s

brother (who also sports the family beak).

Without the hair cuts, differentiating them is nearly impossible.

Meaghan later provided Amy with a snake she had raised

from the

egg, and their friendship fate has been sealed ever since that snake

slithered into Amy’s possession (and promptly into her step-mother’s care,

where it is now used to make house guests feel uncomfortable). Please note,

both Amy and the snake’s bodies will be donated to science. Meaghan plans on

never dying, so that’s a moot point.

Amy grew up a bit, while Meaghan came to terms with the

fact that she never would and promptly began lying on all of her driver’s

licenses. Today, they live together. They found each other once more at the

University of Oregon where they learn about fossils and rocks. Meaghan is a

first-year masters student while Amy is a senior doing original research on

the

cutest fossil mammals,

Omomyids. Meaghan unfortunately has chosen the

paleontological cow-patty minefield that is

Oreodont taxonomy and diversity.

Mary Anning, meanwhile, is still dead. Hopefully, if

things go well, she’s fossilizing as we speak. In the early 1800’s Mary Anning

found the first complete plesiosaur, the first British pterosaur, and she and her brother found the type specimen for ichthyosaurs.

She was one of the most prolific paleontological collectors in history, and she

spent most of her life on the beach scouring it for fossils to sell. She was an expert

in the Jurassic Age marine sediments of England, and despite a lack of

education or money produced many compelling pre-Darwinian ideas as to evolution,

ecology and morphology of these organisms. The paleontologists of the day were

wealthy, white men; she was well known amongst them for finding fossils and

understanding their shape and function. Despite this, Mary wasn’t given credit

for much of what she found or described. She was rarely published, and many of

her ideas were stolen by the male paleontologists of the day. It wasn’t until

long after her death that most of her many contributions to paleontology were

recognized.

Things are getting better, but they aren’t yet fair: out

of the 19 professors on staff in the Geology Department at U of O, only 5 are

female, and only 1 of them is a full-time Geology faculty member.

Country-wide, women still make less than men in the same jobs, performing the

same tasks. Sometimes it’s easy to forget this, or to sweep women into

binders

without much thought. Our culture doesn’t help - women are told throughout

school that they’re not as good at math, not as good at science; they are told that their voices and opinions aren't as important. Whether these messages are

overt or

subtle, the sad fact is that it's 2012 and they still exist.

Fortunately ladies, Meaghan and Amy are here. We're intelligent, charismatic and unsurprisingly pretty good at math. More

importantly, we’re very, very noisy. Ask any of our professors: we’ve got a

lot of things to say (and nobody comes to your office hours anyway so that's not an excuse for cutting our post-lecture discussion off before we're finished, ugh!). In a time when male politicians are vomiting their stupidity all over the news, Amy and Meaghan are stepping forward to cough out opinions of their own (obnoxious, amazing, and otherwise).

We are female, we are scientists,

and we refuse to be ignored. We are Mary Anning’s Revenge.