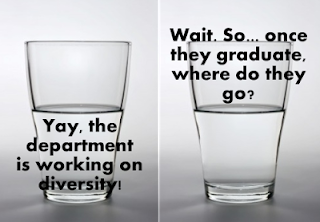

Currently the Geology department at our school is hiring for a new full time faculty position. This is an exciting opportunity for the department to expand the university's breadth of research. It is also an important chance to discuss the presence of women in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields. Currently, the department has 24 faculty listed, not all of whom are

full-time or tenure-track, and 5 of them are female. The graduate

student proportions are much different, about 50:50.

An

article published in 2007 noted that while about half of PhD earners in STEM fields were women, they only held

up to (aka, many schools had less than) 30% of faculty positions. This percentage dropped even further in universities with increased prestige, higher student entrance criteria, larger student body, absence of a women's studies programs, increased research productivity and increased federal funding. Essentially, the more prestigious the school, the fewer lady faculty members they'll have.

The problem is no longer an absence of well-qualified women from

accredited universities - 45.9% of STEM PhD holders in ages 25-39 are

women, though that percentage does vary by field. However, women are

less likely to advance than men and also more likely to leave a position

than their male cohorts. At current rates of hiring and exiting, the

faculty diversity caps out at about 40%, even as the PhD rates continue

to equalize. This is called

demographic inertia: though the amount of qualified women is increasing, the amount of women actually hired and retained isn't.

There are

countless explanations for this phenomenon, some of them asinine, some of them bitter, and some of them unexpectedly and really disturbingly true. Recently our adviser showed us a paper on how

selection bias affects hiring practices. A nationwide sample of biology, chemistry, and physics professors evaluated the application materials of an undergraduate science student who had applied for a science laboratory manager position. All participants received the same materials. The only thing that changed was the gender, with some applications displaying traditionally female names and others male. Participants rated the student’s competence and hireability, as well as the salary and amount of mentoring they would offer the student.

|

| Ladies: too great for mentoring. | |

When faced with a female student, faculty rated the application as less competent, less hireable, and less desirable than the same application with a male name. This preference was independent of the

faculty member's own sex, too - female professors gave the male students just

as much increased preference as the male professors did. The mean starting salary offered to the female student was 26,507.94$. The mean starting salary offered to a male applicant with the

exact same qualifications was 30,238.10$. That's a difference of 3730.16$ for being named Bob instead of Betty, because somehow possessing a penis makes you more equipped to clean beakers.

So what does this mean? If the only difference on the resumes were female vs. male names, can

this whole dilemma be solved with androgynous name choices for future

generations? Sorry future little Scarlett Rebecca Atwater, looks like

it's gonna be Casey, Pat, Jordan, or Morgan for you! But before we all go changing our names to

J.K., there are other choices - and a good thing too, because being named Melvin would cause Meaghan to projectile vomit, and Amy is actually having a near meltdown at the thought of having to respond to her childhood nightmare nickname Amos. For one, shouting this bias from the rooftops might help: there is

evidence that diversity education can reduce both explicit and implicit or subconscious bias.

There are a few ways of altering hiring practices that will help skew the ratio, but even then this is a process that takes time. For most schools, if they begin specifically hiring equal numbers of women it will still take

almost 60 years for their faculty to reach equalized levels. Women leave faculty positions more readily and for a wide variety of reasons including unequal burdens of family responsibilities and discrimination in promotion considerations. Stop this hemorrhage, and faculty positions should reach equal levels

in about 40 years. Combine both of those tactics, and it

only takes 30 years!

That's still a long time, and unless you're a faculty member you might not hold any sway over the processes that will result in change. There are other things you can do. If you're a woman in science, consider

mentoring. If you're a man in science, you should consider being more like

this guy, and participate in groups like

The Good Men Project. If you've got a daughter, send them to

women-friendly science camps. Giving women extra support can go a long way to making them more resilient to the factors that bar success.

|

| Science! Ladies can do it too. And definitely better than Barbie who thinks carrying plastic dinos around is science. |

And remember that talking about it is one of the ways to fix it. Many of our readers are fellow science students that Meaghan and Amy have hassled into reading their blog. Bring this up in lab meetings, bring it up when you're discussing summer jobs. And if you ever get a chance to participate in a hiring process (geology graduate students, we're looking at you!), keep in mind the subconscious bias that might prevent you from suggesting a woman candidate that's equally as qualified as her male counterparts.

WORKS CITED

Cameron, E. , Gray, M. , & White, A. (2013).

Is publication rate an equal opportunity metric?.

Trends in Ecology & Evolution,

28(1), 7-8.

Marschke, R. , Laursen, S. , Nielsen, J. , & Rankin, P. (2007).

Demographic inertia revisited: An immodest proposal to achieve equitable gender representation among faculty in higher education. Journal of

Higher Education, 78(1), 1-26.

Moss-Racusin, C. , Dovidio, J. , Brescoll, V. , Graham, M. , &

Handelsman, J. (2012).

Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United

States of America, 109(41), 16474-16479.

Rudman, L.A., Ashmore, R., Gary, M. (2001).

"Unlearning" automatic biases: The malleability of implicit prejudice and stereotypes.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol 81(5).

Thanks to Dr. Hopkins and Dr. Davis for suggesting some of these articles, and for bringing up the topic in our lab meetings and making us think about it as well.